Written by Grace Rector

Published March 1, 2024

The devastating impacts that European colonization had on indigenous peoples span globally across human history. Here, in modern day Leicester, North Carolina, we, at Durrant Farms wish to respectfully acknowledge the tribal nations whose land we occupy today. We believe that it is important to increase awareness of the true history of colonization’s effect on indigenous peoples whose lands and lives have been taken through centuries of violence, oppression, ethnic cleansing, and broken treaties. According to Native Land Digital, we reside on Cherokee, Yuchi, and Miccosukee land. In writing this post, I would like to acknowledge that as indigenous history was primarily passed down orally, most written history is written from the perspective of the conquerors, and this may lead to the potential for varying accounts of the information and history provided. That being said, the intention of this post is to express the truth of who the Cherokee people are through a brief telling of their origins, history, culture, interactions with European colonialists, and where they are today.

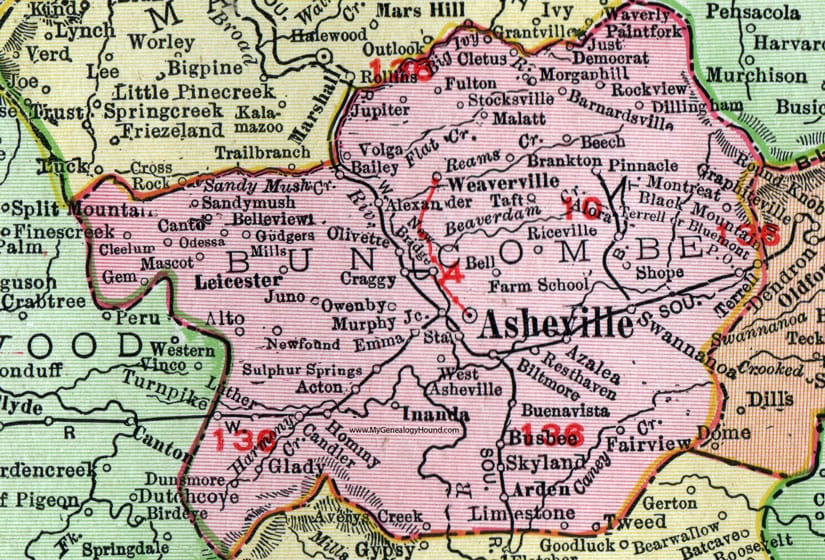

Buncombe County, North Carolina, 1911 Map by Rand McNally via My Genealogy Hound

History of Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee nation was originally located in parts of 8 present-day Southeastern states including Kentucky, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama. According to anthropologists, ethnographers, and geographers, the Cherokee nation have called this land home since the 1300s. The Cherokee people traditionally referred to themselves as Ani-Yun’wiya, meaning the “principal people.” The name Cherokee is accepted today and it is spelled as Tsalagi in their own language. The name, “principle people,” comes from their belief that they were at the center of the world and their purpose was to protect the world through maintaining its state of equilibrium. The Cherokee people saw themselves as a part of the land, rather than separate from it–a perspective that was incomprehensible by the European colonialists and their way of life. They believed that the world came to be after a water beetle dove to the depths of the ocean and pulled up a piece of mud that became land. A giant buzzard then swept through this land and its wings pulled up the soft ground to become the mountains we know today as Southern Appalachia.

The Cherokee people are historically very adaptive to change and new ways of life. Archaeologists have defined two cultural phases that can be connected to the Cherokee people, the Pisgah Phase (A.D. 1000-1500) and the Qualla Phase (A.D. 1500 to Historic times). Life in the beginning of the Pisgah Phase was more nomadic and survival was dependent upon the hunting of long extinct mammals. Later on, with their discovery of agriculture, the Cherokee people began to settle and build permanent housing. By the end of the Pisgah Phase, the Cherokee people had grown into a civilization and that began to shape their culture.

According to archaeological finds along the Appalachian summit, the Qualla phase began in A.D. 1500, before contact was made with Europeans. By this time, the people we know today as the Cherokee, were established hunters and gatherers living in harmony with the land. The Cherokee were once a matriarchal people, meaning the women were the heads of households and were often in charge of agricultural production while men were typically tasked with hunting. Their principal belief system was built around maintaining a balance or equilibrium in the world and this was reflected in the roles of men and women in their society. Men would hunt in the winter and women would farm in the summer. Additionally, balance was maintained through how much was farmed and hunted. The Cherokee would never hunt and gather more than what was necessary for the survival of their people. That is, until European contact impacted their way of being in drastic ways.

Photo by Steve: https://www.pexels.com/photo/selective-focus-photography-of-brown-buck-on-grass-field-682373/

Effects of Colonization

The Cherokee people’s first contact with Europeans occurred around 1540, when Hernando De Soto, a Spanish conquistador, came to North America looking for material wealth. Instead of the riches he was seeking, he, and his expansive entourage, came upon communities of humble people living off the land. Hernando De Soto and others like him were power hungry and used methods of torture, murder, and enslavement to exploit the Cherokee people into giving up riches that they never possessed. Even more devastating, yet semi-unintended, was the onslaught of diseases such as smallpox, bubonic plague, and measles that were brought over from Europe. I say semi-unintended because there were cases in which the spread of disease was used as a method of warfare against indigenous populations. The indigenous people of the Americas did not have the immunity to these dangerous pathogens that many Europeans did, and contracting one of these diseases, more often than not, led to death.

These first interactions with Europeans had drastic impacts on the indigenous populations not only in the Southeast of present day United States, but across North, Central, and South America. According to a 2019 study published in Quarternary Science Reviews, between the years 1492 and 1600, it was estimated that through warfare, famine, and disease, 90-95% of the American indigenous population were killed. That is, 90-95% of the Western Hemisphere was wiped out in a little over 100 years. This holocaust of indigenous peoples continued past 1600 and its effects are still felt tremendously amongst native populations today.

European contact not only led to the onslaught of death and disease among indigenous peoples, but it also drastically changed the fundamentals of their cultures as they knew it. For the Cherokee people specifically, contact with Europeans forced them to abandon many of their traditions. Their belief system that is based around maintaining balance in the world was significantly impacted by European culture. By the beginning of the 18th century, European traders had infiltrated Cherokee villages and were trading European goods, such as metal farming instruments, for deerskins. The traders would “loan” goods to Cherokees for a specific deerskin quota that would have to be met, making it so many Cherokee people were in debt to the traders. The more that European goods were traded and used by the native people, the more they abandoned their own crafts. Eventually, the Cherokee people were dependent upon European trades for necessity rather than luxury. Additionally, the Europeans demand for deerskins began to increase so dramatically that it shifted the traditional mindset that the Cherokee men hunted with–one that respected and cherished the life that was being taken and was conscientious of maintaining harmony in the world. These are just a couple examples of how the Cherokee culture was impacted by European contact.

Arguably, one of the greatest examples of how the Cherokee peoples culture and lives were encroached upon by European colonialism is the forced removal from their ancestral lands, also known as the Trail of Tears. At the end of the 18th century and beginning of the 19th, many deceptive treaties and false land grants were made by the United States with the Cherokee people. After allying with the Cherokee in the War of 1812, Andrew Jackson told the Cherokee warrior and chief, Junaluska, “As long as the sun shines and the grass grows, there shall be friendship between us, and the feet of the Cherokee shall be toward the east.” There were many agreements that promised that the Cherokee people would be their own sovereign state and their land would remain theirs. One policy that was enforced upon the Cherokee people was to become “civilized” by adopting the European/American way of life, forcing them to abandon their own traditions and beliefs. To maintain some semblance of peace, as well as their own sovereign economy, many Cherokee people did assimilate. Even so, Anglo-American settlers of the Southeast continued to push for their removal, especially after gold was discovered on Cherokee land in North Georgia. Coinciding with this discovery, Andrew Jackson became the 7th president of the United States and shortly into his presidency Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830 into law.

In 1835, the Treaty of New Echota was signed and all 7 million acres of Cherokee lands in the east were ceded in exchange for land in modern day Oklahoma and money to get there. This treaty was opposed by the majority of the Cherokee people and many resisted their removal from their ancestral lands. In the spring of 1838, 7,000 United States troops were sent to forcibly remove the Cherokee people, placing them in concentration camps to await their forced displacement. In the Autumn of that same year, about 16,000 Cherokee people were forced to trek 1,200 miles westward on foot, thus beginning a route known today as part of the Trail of Tears. Due to starvation, disease, exhaustion, and inclement weather, it is estimated that 10 to 25 percent of the Cherokees who made the journey died en route.

Photo by Raychel Sanner: https://www.pexels.com/photo/green-tree-under-white-clouds-4824517/

Cherokee Nation Today

Today, the majority of Cherokee people can still be found in Oklahoma and according to the official Cherokee website, “…under the leadership of the Principal Chief, the Cherokee Nation continues to exercise its treaty rights, sovereign authority, and jurisdiction over the Cherokee Nation Reservation and to strengthen its institutions of tribal governance for the benefit of the Nation’s greatest resource—its citizens, their children, and the future generations of Cherokees.” There are still Cherokee people that reside in the Southeast today known as the Eastern Band of Cherokees–descendants of natives who were able to hide in the mountains and escape removal. The Eastern Band of Cherokees reside in what is known as the Qualla Boundary, 57,000 acres of land in Western North Carolina that was bought back by tribal members in the late 1800s, only a very small fraction of the 7 million acres that the Cherokee once resided on here in the Southeast. The Eastern Band of Cherokee people who reside there today are working to keep their history and culture alive while maintaining a strong and caring connection with their land.

Durrant Farms plans to support the Eastern Band of Cherokees and the general indigenous population of the United states in the following ways: We will continue to educate ourselves and work to raise awareness of who the Cherokee people are and how colonialism affected indigenous populations across the globe. We plan to purchase books and other crafts curated by Cherokee people to be shared at our farm with our guests. As a team, we plan to visit the Qualla Boundary to witness first-hand who the Cherokee people are and how they live today. Below, you can find links to further educational resources and various ways in which you can support the Eastern Band of Cherokee people.

Sources:

The Treaty of New Echota and the Trail of Tears | NC DNCR

Perdue, T. (1989). The Cherokee (Indians of North America). Chelsea House Publishers.

Mails, T. E. (1996). The Cherokee people: The story of the cherokees from earliest origins to contemporary times. Marlowe & Company.

Elish, D. (2002). The trail of tears: The story of the cherokee removal. Benchmark Books/Marshall Cavendish.

Resources for Further Education:

Land Reparations & Indigenous Solidarity Toolkit – Resource Generation

Fostering Indigenous Knowledge to Help Mitigate Climate Change – The Laurel of Asheville

Conley, Robert. A Cherokee Encyclopedia. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2007.

Duncan, Barbara R. and Brett H. Riggs. Cherokee Heritage Trails Guidebook. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Organizations you can support:

Education and Consultation – Center for Native Health

Eastern Band of Cherokees Community Foundation

Indigenous Environmental Network